From the first moment The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch arrived on my desk, it was clear that this project would be a chance for me to do a lot of learning.

I came into it having forgotten almost everything I was taught about Reconstruction — which was very little to begin with. I remembered learning that the whole thing had sort of ended in failure. And I remembered the terms “carpetbagger” and “scalawag,” though I probably couldn’t have told you very convincingly what they meant. And that was about it. But as I quickly discovered in working with Chris Barton’s manuscript, Reconstruction was an incredibly fascinating — and formative — period in American history. Another thing became immediately clear to me, too: the strength and clarity of Chris’s vision for the story.

He knew the story he wanted to tell — the story of an enslaved teenager who became a US congressman in only ten years — and he knew the importance of telling it, how the story represents both the failures in our country’s past, as well as its promise and potential.

I see a lot of projects that transform radically from start to finish, but with John Roy Lynch, nearly all of the essential elements present in the final book were there from the beginning.

That’s not to say, of course, that the project didn’t change.

In the earliest versions, for example, Chris had written John Roy Lynch in a sort of verse:

John Roy Lynch

had an Irish father

and a slave mother.

By the law of the South

before the Civil War,

that made John Roy and his brother

half Irish

and all slave.

The verse format draws attention to the parallelism, the repetition, and the contrasts that make the language throughout the book so eloquent — and I think it was an important step in helping Chris craft the story. But fairly early on we all agreed that the short lines also gave this story a sort of stilted feel that distanced the reader and felt distracting. Taking out the line breaks fixed that, helping the text find a fine balance between that poetic feel and the sort of conversational tone that makes this complex story accessible to young readers.

We worked hard to get that tone just right, and to make sure that everything was as clear as it could be. We went over every word in this book at least once . . . or twice . . . or twenty times. Chris and I had one long conversation just about whether or not the wording “[the southerners] quit the United States and formed their own country” was too colloquial. In the end Chris convinced me that it perfectly captured the petulant sort of school‐yard pettiness that he wanted to show. And illustrator Don Tate, too, offered his authorial insight (not just his wonderful illustrations) in more than one place. He was the one (thankfully) who pointed out that it really should be “enslaved people” rather than “slaves.”

The hardest work for me, though, came in getting the book’s last four spreads just right. They follow the spread of Lynch making his rousing speech to the US House of Representatives — an inspiring moment that left me wondering, where do we go from there? How do we draw this book to a close?

Chris’s original ending read this way:

If John Roy Lynch had lived 100 years (and he did come close), he would not have seen that day. In fact, some would say, we’re still waiting — but we have come close. And perhaps he can bring us closer still.

John Roy Lynch represented the people of Mississippi in the 1870s. But not only them, and not only then. He also represented — and he represents — the promise and potential of America itself.

That’s compelling stuff. It’s fierce; it’s beautifully structured; it’s inspiring. But after a lot of read‐throughs, it also came to seem a bit heavy‐handed. The switch to first person plural pulls the reader out of Lynch’s story. Instead of letting Lynch’s life speak boldly for itself, these final lines tell readers exactly what they should take away. That powerful finish risked being a bit too didactic.

But coming up with an ending that could equal that eloquence was not easy. We asked a lot from that final page. It needed to transition readers away from the speech on the previous page. It needed to hint at the long life Lynch would go on to have. It needed to acknowledge both the hopefulness and the failure of Reconstruction. Finally, it needed to draw readers gently in toward the meaning by means of the story, rather than pulling them away from the story with a message.

I suspect Chris might have gotten a bit sick of all my fussing over the ending. At one point he sent me ten different alternate endings at one time. I think maybe he might have been daring me to not at least find one of them satisfying.

(We went through a few more versions after that anyways.)

It wasn’t until fairly late in the process that we talked about adding a historical note — and that actually helped solve the problem of the ending page. The historical note would be placed facing the final page of the narrative, serving as both an extension of it and a separate piece. This would allow John Roy Lynch’s story to stand on its own, but it would also enable us to provide a bit more explanation about exactly why that story should be important to readers today — to draw out the themes of the book and set John Roy Lynch’s life within its complex historical context.

Setting John Roy Lynch’s story within its historical context was essential for this book. Chris is right that it’s probably in large part the complexity of Reconstruction that prevents the era from being covered better in schools. It was critical for us to be able to make Reconstruction understandable for younger readers.

When we started working with the backmatter for John Roy Lynch, I’d just finished working on The Right Word — another book where we labored long and hard over the backmatter. In that book, we had included a two-page timeline, and we thought a similar element could work well to document John Roy Lynch’s life. For the timeline in The Right Word, we had included a number of events besides Roget’s life, events that showed how his age was one of discovery and invention.

But when Chris put together a rough outline of events that could be included on a timeline for John Roy Lynch, though, he sent me five pages of material. It was clear we wouldn’t have room for anything extra — we’d have more than enough material just trying to lay out the basic events of Reconstruction. We cut it down, and then cut some more, trying as hard as we could, word by precious word, to make all the complicated history fit onto two pages. At one point Chris emailed me, sure nothing else could be cut. “Maybe we can go with 8pt. type,” he suggested, “and package the book with a magnifying glass?”

We didn’t fit everything in, of course. Not even with a historical note,

a timeline,

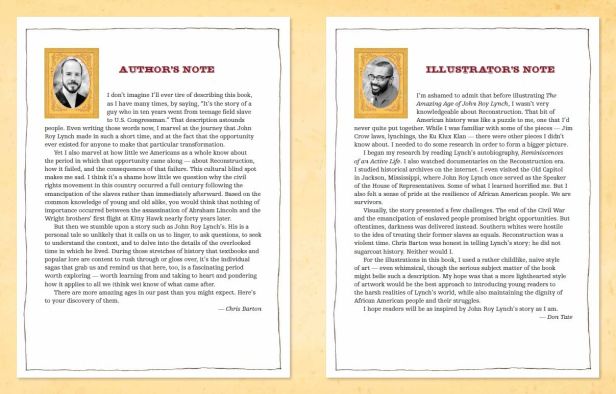

an author’s note, an illustrator’s note,

a list of further reading, and a map.

But I hope that we fit enough into both the story and the backmatter.

I hope, too, that in the end we’ve crafted a book that captures the extraordinary life and character of John Roy Lynch — a book that tells one remarkable man’s story in a way that will help readers understand a complex and important part of history — a book that will inspire them to work for the peace and the justice that John Roy Lynch never stopped fighting for and that we still haven’t quite achieved.

I’ve recently read this book and was ‘taken in’ by a feeling that this complex book had been heavily edited for the finding the ‘correct words’. Now, when I read all that went into this final book, I’m going to read it again and pay closer attention to how these key events and phases were handled. Just had a sense that this was a ‘solid’ book, and yet Chris Barton and Don Tate made it look so easy. Thank you for this post. It was a great read.