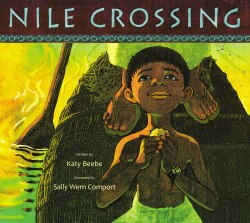

For the last month or two, those of us here at EBYR have been putting the final touch on the books for our Fall 2018 list. The last book to get sent off to the printer (and thus the one taking up the lion’s share of my thoughts recently) was Nile Crossing, the second book from Katy Beebe, author of Brother Hugo and the Bear. It’s a book about a young boy who is starting his first day of school—but he lives in ancient Egypt, and will be studying to become a scribe.

As an editor, I’m often asked what I’m looking for in new projects. This is a difficult question to answer, of course, and the truth is that I’m hoping to see the projects I would never have dreamed of asking for. More often than not lately, I’ve been pointing to Nile Crossing and Brother Hugo and the Bear as examples of this.

Not only do each of these books have a fabulously unique premise that sets them apart from any other children’s books available, they also each have something else: a strong, distinctive narrative voice that holds the stories together and makes them work.

Followers of this blog may remember that I wrote a post some time ago on what makes voice work in narrative nonfiction. I wrote about how the author’s voice in narrative nonfiction has to convey authority, it has to show, not tell, it has to be appropriate for the subject and intended reader, and it has to use vivid, intentional language.

In fiction, the author’s voice has to do much of the same work. I want to illustrate that here by looking at the opening passages from Brother Hugo and from Nile Crossing.

* * *

It befell that on the first day of Lent, Brother Hugo could not return his library book. “I shall have to inform the Abbot of this, Brother Hugo,” said the librarian.

The Abbot was most displeased. “Our house now lacks the comforting letters of St. Augustine, Brother Hugo. How did this happen?”

“Father Abbot,” said Brother Hugo, “truly, the words of St. Augustine are as sweet as honeycomb to me. But I am afraid they were much the sweeter to the bear.”

“Bear, Brother Hugo?”

“Yes, Father.”

“Pray tell, Brother Hugo,” said the Abbot, “how did a bear find our letters of St. Augustine?”

“They seemed to agree with him.”

For Brother Hugo and the Bear, Katy Beebe uses a wry third-person voice that captures a distinctly old-fashioned flavor well-suited to a story about medieval monks and manuscripts. The tone is somewhat formal (“shall have to inform” and “was most displeased”)—appropriate to the subject and the story—but not inaccessible for children—appropriate to the intended reader. Notice how even those first two opening words (“it befell”), so intentionally chosen, immediately pull the reader into Brother Hugo’s world—a world that may feel somewhat unfamiliar to them. And like the story, the language is also playful—especially that last line, where Hugo’s response to the abbot plays on the dual possible meanings of “how did a bear find our letters?” The author doesn’t have to tell us that Brother Hugo is a little hapless—she shows us through the dialogue.

For Nile Crossing, Katy Beebe uses a very different voice:

We wake in the still darkness

of a day unlike all others.

I roll up my mat, and my heart

swoops like a falcon in this new

day, the first day of school.

In the flickering glow of the lamp,

Mother knots an amulet around my wrist.

To keep me safe, she says with a kiss.

It is a scarab, my name, Khepri.

She tucks three honey cakes into my belt.

A treat for later.

Notice that for this book, Katy has chosen a first-person voice. Nile Crossing is a story that all takes place within the space of an hour or two, and the voice that Katy uses works to draw the reader into that hour, into Khperi’s experience and emotions. The language is appropriately impressionistic, using vivid, concrete, evocative images to help us see things through Khepri’s eyes—a heart swooping like a falcon, a lamp flickering, three honey cakes tucked carefully into a belt. The language is also less formal than in Brother Hugo—appropriate for words spoken by a child—but it is still not too casual. After all, Khepri is apprehensive about what awaits him—and he is also about to embark on a grand new future.

Each of these books has a very distinct voice created through the words, images, and rhythm the author has chosen. But both books use that voice very effectively to pull the reader into the characters’ experience, into a world that may be unfamiliar at first, but brought to life through language.

* * *

* * *

Kathleen Merz is managing editor for Eerdmans Books for Young Readers. Read her From the Editor’s Desk column — packed with editorial insight and behind-the-scenes info on Eerdmans books — one Thursday a month here on Eerdlings.

Nile Crossing definately sounds like a book for me. Thanks for the look into voice!